This living roof is a home for plants and wildlife – right in the city

One San Francisco project demonstrates how rewilding can be supported in the unlikeliest of places.

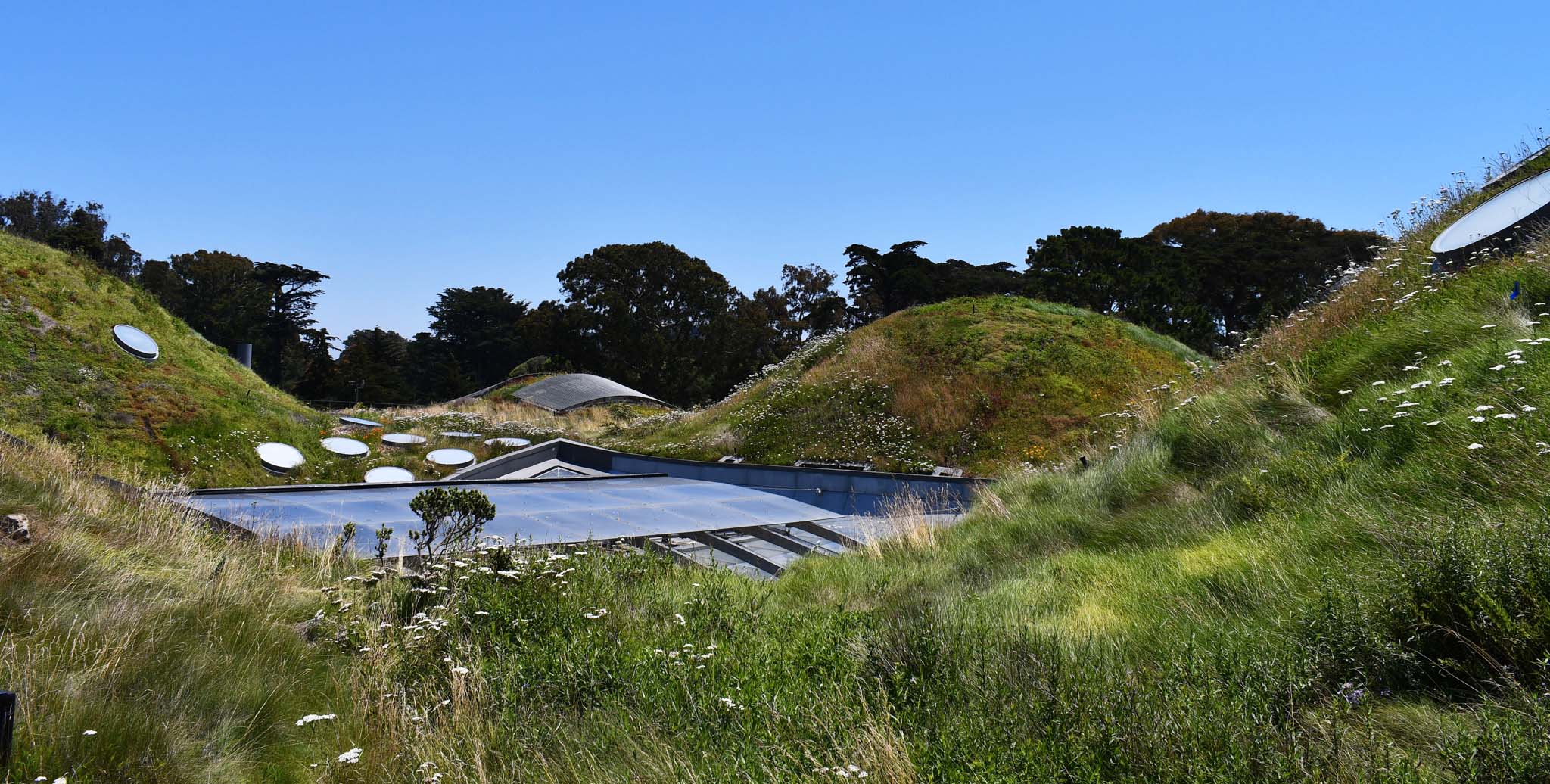

I’m standing in front of rolling hills filled with the densest concentration of native wildflowers in all of San Francisco, marvelling at the diversity of plants and insects before me. As the fog recedes toward the distant ocean, butterflies and white-crowned sparrows flit about in the July sunshine, busy with their day. A baby bird hops around beneath a small shrub, completely unperturbed by my presence. Suddenly, I’m startled by the sound of an elevator opening and a gaggle of excited kids spilling onto the platform. Here in this nature-filled space, it’s easy to forget that I’m actually 15 metres (50 feet) off the ground in Golden Gate Park, on top of a science museum.

Landscape botanist Rachel Alexander rushes over to meet me after a morning spent mulching the museum’s ground-level gardens. She usually comes in before the California Academy of Sciences opens so she can use the only elevator to the roof without competing with visitors. Down below in the museum, it’s chaos. The hum of hundreds of excited tourists is punctuated by the screams of delighted children. If you catch the roof between groups of visitors, it’s a quiet reprieve from the ruckus below.

At first glance, the living roof accomplishes architect Renzo Piano’s vision to “lift up a piece of the park and put a building under.” But the tireless efforts of landscapers including Alexander and her teammate Nikol Soluski make this much more than just an architectural feat. Soluski is proud to tell me that this one-hectare (2.5-acre) rooftop oasis has become one of the largest places for animals to touch down, uninterrupted by chemicals and humans, from Monterey Bay all the way to Marin – a distance of about 190 kilometres (119 miles). Though the living roof is small in comparison to other whole-landscape rewilding projects, the hidden secrets and history of this patch of green hold inspiration and lessons for small-scale rewilding efforts in cities everywhere.

Designing for good

The living roof came into existence as part of a full rebuild of the California Academy of Sciences in 2004. Earthquakes and decades of use – the Academy is the oldest scientific institution in the American West – meant that the building was due for an upgrade both structurally and practically. Piano, by then a renowned architect, wowed the board with his architectural instinct, and he and his team were soon creating what would become one of the world's largest and most sustainable buildings.

The facility relies on a structurally derived passive heating and cooling system and was built with recycled and local materials where possible. It features a stunning open floor plan where two large domes – one a rainforest and the other a planetarium – flank a covered piazza. Even the insulation is resourcefully assembled, giving new life to discarded denim. All of this sits atop an underground aquarium, with ground-level tide pools giving you a hint at the watery wonders below.

The cherry on top is the living roof, which is not only a beautiful and iconic exhibit but integral to the green building’s function. The roof’s seven hills – an homage to the seven hills of San Francisco – help cool the museum’s interior as cold air is funnelled down through retractable ceiling panels into the piazza. When the new building opened in 2008, it was considered “the largest living roof in California and the most complex living roof ever constructed.”

The two largest hills on the roof, which the rainforest and planetarium domes sit under, are covered in circular glass portals. These windows let in light for the rainforest and, when open, further regulate the indoor temperature by letting heat escape.

This roof design was structurally required to support millions of pounds of soil, water and plants, and nothing about manifesting it came easily. On top of the concrete, an additional seven layers were added, forming a complex rooftop lasagna with a range of functions, from waterproofing to filtering to insulation. Because rain is often scarce in California, there’s even a layer that helps to absorb and store water. Of course, due to weight, there can’t be too much water stored on the roof, so a grid of lava rocks guides excess down the hills toward the perimeter drains. All of these measures result in the roof keeping up to 7.5 million litres (two million gallons) of runoff out of city drains each year. In addition to rainwater, the roof is irrigated nightly with greywater from Golden Gate Park.

Building a native landscape from scratch

The original vision for the roof was, ultimately, an experiment. Piano pictured the space covered in a simple green mat. The growing medium was designed to be lightweight and shallow, so only nine native species of ground cover were chosen for the first plantings. Fifteen years on, the museum is settling into a long-term plan.

Through the years, Alexander, Soluski and their predecessors have evolved the roof into something close to a coastal prairie ecosystem. Because the prairie is elevated, it’s not what would naturally grow on the ground – and of course there are no grazers – but it does offer a glimpse into what San Francisco might have looked like before the built environment dominated the landscape.

The roof’s undulating hills create microclimates no longer seen in the city, allowing for sensitive native species such as the dune pansy to thrive. Historically, the San Francisco Peninsula was covered in sand dune ecosystems supporting not only such plants but also pollinators, many of which are now beleaguered or extinct.

Taking in the abundant biodiversity from the viewing platform, the landscape on the roof feels ancient and untouched. But for Alexander and Soluski, it’s a constant experiment to see what will survive in the different microclimates. With steady exposure to sun and wind, the plants need to be hardy and well-adapted to the salty ocean air. Currently, more than 90 species of California native plants grow on the roof.

We leave the platform and wander through knee-high grasses. Alexander excitedly points out all of the plants, stopping abruptly to ask whether I’m afraid of spiders. Jumping spiders abound, but she says not to worry. “They mind their own business; they have so many things to do up here.”

We stop frequently to inspect a bug, flower or seed head. Yarrow seems to do well, its white flowers scattered across the roof. Red fescue, a native grass, thrives in the shade of the hills and waves gently in the breeze like seagrass in a tide. California aster is the most common native plant on the roof and is a bountiful host for insects and pollinators such as the northern checkerspot, field crescent and pearl crescent butterflies.

Originally, the roof had 15 centimetres (six inches) of soil, limiting what could be grown. As staff continue to change the dynamic of the living roof by adding more shrubs and taller varieties of plants, they’ve needed to increase the amount of organic material. Still, the largest plants the roof can support are waist-high shrubs – and even those will sometimes blow over in heavy winds. Trees find it difficult to grow in such shallow soil but will occasionally take root anyway. At one point, five stowaway willows were found growing on the roof, a dangerous surprise. Willow roots tenaciously follow water sources and in the past have found their way into the irrigation system, breaking the piping.

Every rewilding effort has its share of lessons and challenges, but the living roof lies at the intersection of the built world and the natural world, which can be as frustrating as it is inspiring. Soluski and Alexander find themselves in a constant conversation with invasive species that find their way here. Alexander suspects that most seeds arrive by way of birds, wind or people unintentionally trekking them in.

While pointing out the non-native strawberry and blackberry species, Alexander reflects on how interesting it is to see what will grow here. Rather than approaching the project with a rigid end-state in mind, she and Soluski seem to be guided by their curiosity as they steward the space and adapt to the constant changes.

Their latest surprise? Red-tailed hawks have been nesting in the nearby cypress trees; their adolescent offspring are using the living roof as a safe space to learn to fly.

Looking for potential

Though the living roof has been well received by the public, Alexander notes that it can be difficult to change people’s perception of how a wilder landscape is meant to look. In midsummer, for instance, many of the grasses are going to seed, their long brown stalks and seed heads a natural part of the roof’s life cycle. Visitors, however, sometimes see these muted colors and assume it’s poor maintenance.

“Brown is not a very universally loved colour in landscaping, unfortunately,” Alexander says. “But it’s really important for there to be these seasons. Wild needs to be more accepted, especially since this is supposed to be a safe space for travelling wildlife.”

For the living roof and those who sustain it, there’s no definitive end to the project. Like many places, the process is dynamic, a reflection that adapts as we learn more about a wild space – and our place within it.

Despite the challenges and unanticipated design flaws, today’s stewards hold no hard feelings toward the roof’s creators. All stages, from the visionary plan to the dedicated maintenance, have made this place the inspiring wildlife corridor that it is today. “They designed something that has so much potential,” Alexander says. “So we’ve been trying to manifest all the potential that we can.”

Comments ()