Putting cities at the heart of rewilding

Urban rewilding doesn't just help cities and their residents. It's good for the rest of nature, too.

It is tempting to think of rewilding purely in terms of rural landscapes. But cities are where nearly all of us live. The city landscape is something we have to get right. Nature-based solutions answer almost every serious problem our cities face. Putting cities at the heart of the rewilding vision is one of the most important steps we can take for the future. Thinking holistically, as rivers help us to do, brings cities into context with mountains, farmland, green belt, wetlands and forests. Creating flow between a city and its hinterland, turning grey into green and blue, connects the solar plexus of human life with the rest of its physical body.

The economic incentives for urban rewilding are abundantly clear. Properties on tree-lined streets – just one example – have a higher value than those on predominantly grey streets. The trees themselves save the taxpayer money in terms of public health, reduce the costs of air conditioning and heating, and help in national and global efforts to mitigate climate change.

The more green spaces there are in cities, the more accessible nature and its benefits are to all levels of society.

But what rewilding brings to society in terms of fairness and inclusivity is often overlooked. Urban rewilding brings all demographics together. The more green spaces there are in cities, the more accessible nature and its benefits are to all levels of society. One of the greatest inequalities in society is health. Rewilding can improve living conditions and mental and physical health for everyone, but particularly for those living in deprived areas.

Rewilding can create jobs and volunteering, and build communities. In Medellín, Colombia, the city’s low-income citizens are given training to become gardeners and ecologists to look after their green corridors. Free Town in Sierra Leone pays its citizens to plant trees. In Paris, residents actively participate in the greening of their city. Just as in the countryside, rewilding can regenerate degraded areas, bringing life back in. In Metropolitan Detroit, abandoned, depressed, post-industrial areas along the river have been transformed into a river walk described as a ‘beautiful, exciting, safe, accessible, world- class gathering place for all’. Nearly three million visitors now use it every year, strolling between the city and the Great Lakes.

Education is one of the most important roles rewilding can play in the urban environment, bringing an appreciation for nature into the lives of city residents. This is, arguably, where a shift in thinking can reap the most rewards. Places where populations are densest can create a groundswell of support for nature recovery and action for climate change. They can exert pressure on governments and councils, driving an unstoppable force for change. No single city is providing all the solutions. But many are leading lights, exploring courageous, imaginative new ways to transform our cities. Rewilding can bring all these ideas together, holistically. Embracing a new vision for sustainable life in our cities will radiate hope for nature’s recovery in every corner of the globe.

According to scientists, the negative impacts of climate change are mounting much faster than predicted and are already hitting the world’s most vulnerable populations in devastating ways. UN secretary-general António Guterres calls this a ‘damning indictment of failed climate leadership’. On the current trajectory, the impacts will soon be irreversible. It is now or never, according to scientists, to limit global warming, conserve global biodiversity and set in place strategies for the sustainable use of natural resources. Systemic change is needed right now.

Politicians are proving slow to act. The kind of change that is needed can only be achieved by an upwelling of global public action. Most pivotal moments in history, the radical changes that have advanced the course of human thinking and enlightened our collective behaviour, have happened as a result of an irresistible surge from grassroots. As citizens of the earth, it is up to us to drive the agenda, to change the mindset of the institutions that govern us.

At the same time, there are things we can do ourselves. The late, great American biologist E. O. Wilson told us that, if we are to save earth’s life-support systems on which all species – including our own – depend, we must dedicate half of all terrestrial land to nature. How on earth do we do that, when so much of our land is depleted and fragmented? Rewilding is one of the most positive and exciting answers to that question. Across the world, rewilding projects have proved that nature is ready to respond, even in the unlikeliest of places. Rewilding shows how to ignite the natural processes and reinstate the creatures that restore ecosystems. If we do it in the right way and let nature take the lead, humans can be a keystone species, drivers of biodiversity, creators of habitat, repairers of damage.

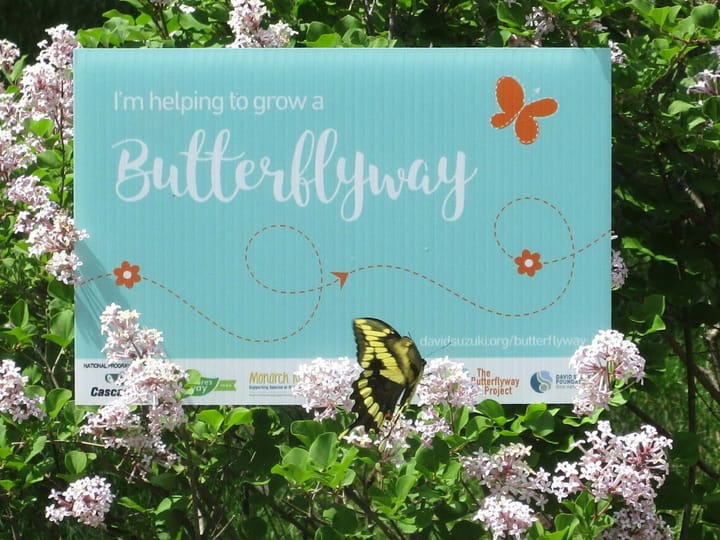

Scale is important. But still more important is connectivity. The tiniest piece of land can make a vital difference if it relates to other patches of nature, helps to join the dots. Whatever scrap of soil we have agency over, whether it’s a field, a grass verge or a window box, can make a difference. Opening our hearts to a wilder world, letting nature in to our backyards, increasing the potential for life on every inch of soil, is the key to our future. At Knepp, as we watch the rewilding movement grow, it feels as though the tendrils of change are spreading like mycorrhizal fungi fizzing with connections, fuelling the determination of individuals and communities from mountaintop to sea, from village green to city street. A wilder, more resilient world is within our reach.

Excerpted from The Book of Wilding: A Practical Guide to Rewilding, Big and Small. Used with the permission of the publisher, Bloomsbury. Copyright © 2023 by Isabella Tree and Charlie Burrell.

Comments ()