The group spreading native seeds, one packet at a time

Minnesota's MnSeed Project is boosting biodiversity by collecting, saving and planting native seeds – and teaching others to do so, too.

Minnesota’s MnSeed Project was inspired by the global seed shortage in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic. As people turned to their gardens to find solace in uncertain times and attempt to avoid food shortages by growing their own, demand for seeds outstripped supply.

“All these seed companies were running out of seeds,” says Courtney Tchida, co-founder of the group.

The answer seemed simple to Tchida and friends Stephanie Hankerson, a nature educator, and Dawn Lamm, founder of the Como Community Seed Library. “Teach people how to save seeds, themselves,” Tchida says.

The project kicked off in 2020 as a subsidiary program of the Minnesota State Horticultural Society, where Tchida was working at the time. The trio started organizing events and webinars on how to collect, save and plant native seeds.

But their big break arrived after they received an invitation to a seed collection event hosted by 21 Roots Farm, a three-acre restored prairie in Washington County, Minnesota, a suburb of Saint Paul. That event came with a nudge from the Capitol Region Watershed District to apply for a partnership grant. This success was further solidified when in 2022 they were awarded the Capitol Region Watershed District Outreach Program of the Year award.

Now independently run, the MnSeed Project continues to create a free, locally adapted native seed economy through collecting, saving and preserving seeds. The group are so passionate about this that all the seeds they collect are given away for free at workshops they host and events they attend, such as seed swaps.

For Tchida, seed saving is a natural outcropping of her lifelong exploration of finding ways to support the environment. “This is such an obvious and easy way,” she says. “The connection you make intrinsically with the plants throughout their whole growth process is so much fun.”

What Tchida, Hankerson and Lamm do may be fun, but it also makes a real difference to the Saint Paul region. In Minnesota, 130 native species are reported as being endangered, including pollinators such as monarch butterflies, rusty-patched bumblebees and little brown bats. According to the Department of Natural Resources, one of the reasons for the state’s losses is habitat deprivation due to development. Replanting pollinator pathways with native seed creates new habitat.

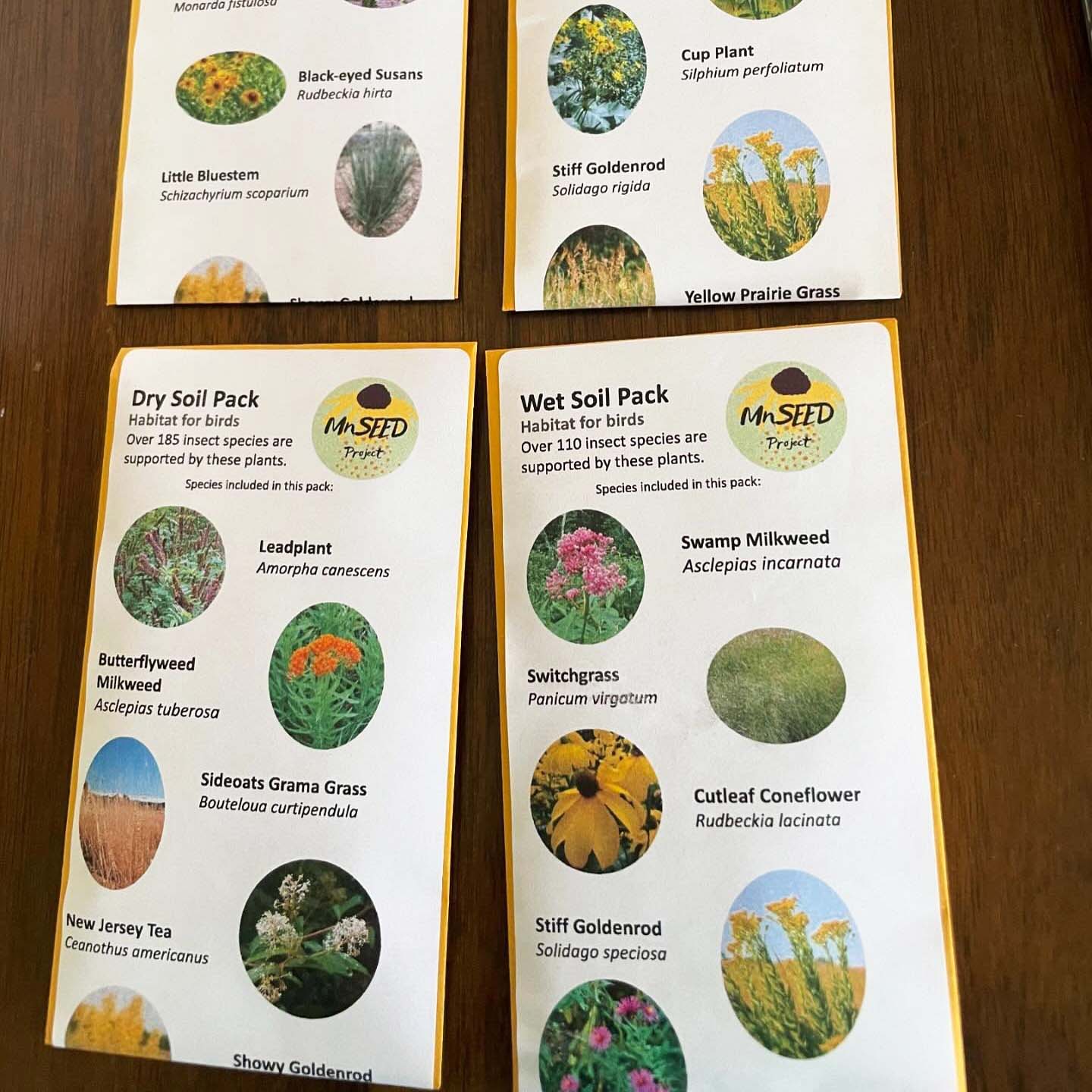

In 2023, MnSeed collected a whopping 14,000 seed packets from the Capitol Region Watershed, which includes the land surrounding lakes, rivers and streams flowing through the area into the Mississippi River. They saved seeds from more than 150 local plant species, including native prairie grasses and flowering plants. The amount of seed in each packet varies, but it can be significant: bear in mind that one Echinacea purpurea plant can yield 500 or more seeds depending on how many blooms it produces during the growing season.

Of course, the group never take all the seed heads when they forage. “The maximum we will collect is 20 percent of the seed heads present,” Tchida says. The rest are left for nature, to provide food for wildlife and to self-seed in place.

The team are also picky about their seeds, especially when collecting from home gardens. “We don’t mess with any of the cultivars or nativars,” Tchida says. These are plants that have been bred for enhanced appearance or longer blooming times and may not offer the same ecosystem benefits as true natives.

Seed saving 101

One of the groups MnSeed works with is Frogtown Green, a resident-led volunteer organization working to establish a two-and-a-half-mile pollinator pathway along the swale of Pierce Butler Road in Saint Paul’s Frogtown neighbourhood. The group realized that collecting and propagating seeds from home gardens would help their efforts, and so they connected with MnSeed.

“The Bee Line is envisioned as a pollinator-friendly garden that defines Frogtown’s northern boundary,” says Patricia Ohmans, co-director of Frogtown Green, of their project. “The whole point is to demonstrate the beauty, hardiness and climate appropriateness of native plants. Without native seeds, we can’t do that.”

Collected seeds are first cleaned, often with a seed aspirator. This machine is similar to a vacuum and sucks the chaff (dirt and husk) from the seed. This process, sometimes referred to as winnowing, can be adapted by the home gardener by using a sieve or wire basket and tossing the seeds up in the air. The motion and any breeze work together to remove the debris. There are other methods, too. Tchida has demonstrated on the group’s Instagram page how to use an old blender to break up tightly clustered seed heads containing dozens of seeds. Then, of course, dancing or stomping gently on seed heads will also break them up.

Now the seeds need to be dried. The best way is to lay them on a paper towel in the open air. Once completely rid of moisture, seeds can be stored in porous paper bags or glass jars in a cool, dry and dark place until ready to be propagated. Seeds saved this way will last a long time. Echinacea seeds, for example, can remain viable for planting for up to two to three years if stored properly.

The milk jug method

“I’ve learned a lot from MnSeed,” Ohmans says. And there’s always a new skill to pick up. This winter, the MnSeed Project is holding workshops on how to germinate seeds using a milk jug, a technique known as winter sowing. Many seeds native to cooler climates, such as those found in Minnesota, require time in the cold so they can break their dormancy and sprout.

A clean four-litre/one-gallon milk jug (or similar container) with large holes in the bottom for drainage makes the perfect vessel for this technique. Add soil, plant your seeds and place the whole thing outside in wintertime where you’d like the plants to permanently grow. This enables the seeds to get the cold stratification they need. When the weather warms up, the milk jug becomes a mini-greenhouse, expediting the germination process.

For Ohmans, one of the most exciting things she’s witnessed about seed saving is people’s enthusiasm for it. Tchida has seen this too. One of her favourite events is the group’s annual presence at a local apple festival. “We bring seeds collected throughout the season, take over all the picnic tables and have a communal seed-cleaning event,” she says. People come by, ask questions, get involved and don’t want to leave.

What does the future hold for the MnSeed Project? Tchida envisions more workshops and more seed collection, of course, as well as working with groups such as farmers to plant conservation areas of native seeds and pollinator pathways.

As for anyone else curious about saving native seeds and even starting a local group of their own? “Do it,” she says. “It’s so much fun.”

To learn more about how to collect and preserve seeds visit MnSeed Project’s Instagram page @mn_seed_project.

Comments ()