The return of the bison

European settlement drove plains bison out of the North American prairies. Can rewilding bring them back?

It was a little like chasing ghosts. Every trail was pulverized with fresh hoofprints, peppered with fresh dung and plastered with fresh mats of fur, as if a stampede had roared through only seconds before. I could even hear them at times, grunting methodically as they tore at grass somewhere within earshot or moved in urgent masses from one pasture to the next. But I couldn’t see them. Their steepled shoulders and dangling jaws were somehow lost among the stumpy spruce of Elk Island National Park in Alberta, Canada.

Here again, I thought, was the vanishing act of plains bison (Bison bison bison), departing so suddenly that the ground was still warm, the air still musky. It’s a trick they’ve pulled before: defining the Great Plains from Alberta to Mexico as recently as 1800 and then, less than a century later, roaming nowhere outside fence, story and song.

We can’t say how many there used to be. Twenty-five million is an oft-repeated estimate, but more visceral are stories of people riding for days to circumnavigate a single herd, or of entire landscapes smothered beneath bison biomass.

One encounter near Last Mountain Lake, Saskatchewan, was described by Isaac Cowie of the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1869.

“We fell in with buffalo innumerable,” he wrote. “They blackened the whole country, the compact moving masses covering it so that not a glimpse of green grass could be seen. The earth trembled day and night, as they moved in billow-like battalions over the undulations of the plain.”

By 1881, this wild herd – in fact, all wild herds – had been destroyed north of the 49th parallel, that long, straight border between Canada and the U.S., while those south of the line were reduced to a few pitiable flocks totalling perhaps 1,000 individuals. An unregulated market hunt collided headlong with a shifting climate, introduced disease, habitat loss and a culture of spectacular waste, all but obliterating plains bison from the Earth.

Elk Island National Park is one of the precious few reasons they still exist. In the final days of the 19th century, a handful of entrepreneurs collected the last of the world’s wild bison onto ranches throughout the United States. The most famous of these groups was the Pablo-Allard herd in the Flathead Valley of northwestern Montana. It was built of local bison, supplemented with specimens from Saskatchewan, Texas and Kansas. Today, 80 percent of all bison are direct descendants of this heroic hodgepodge.

Around 1904, the Canadian government purchased Michel Pablo’s half of this herd, 800 animals earmarked for the newly christened Buffalo National Park near Wainwright, Alberta. But the park wasn’t quite ready for them, so these bison enjoyed a layover in Elk Island. Because they were popular – and because they were overlooked – a few dozen never left.

Buffalo National Park became an underfunded quagmire of disease, mismanagement and overpopulation; it closed in 1939 when its remaining bison were euthanized. The lucky few left behind in Elk Island became Canada’s de facto “seed herd,” its members used to establish new herds in turn.

Elk Island is where Canada assumed responsibility for a species – and not just any species. This one was an ecosystem engineer, shaping prairies to the benefit of land and beast. It was mobile, accustomed to absolute freedom in one of the largest continuous ecosystems on the planet. And it was prolific, with herds enjoying an average annual growth rate of 20 percent. Somehow, these animals were to be kept healthy and wild in the modest spaces allotted to them, behind fences and cattle guards.

I finally did find bison in Elk Island. After a fruitless morning on foot I drove by a small herd grazing in the rain. They stopped and stared, circumspect, water dripping off flanks and horns, ready to vanish once more into surrounding timbers. I had to respect their caution, descended as they were from survivors among survivors – wild animals whom we manage from cradle to grave. And not just here.

The overwhelming majority of living bison suffer this contradiction in terms, wild in practice if not reality. I lingered long enough to take a few photos, then steered for other “wild” herds. Namely, those of Saskatchewan.

Where people replace predators

Grasslands National Park in Saskatchewan is the archetypal prairie. Its hills are whipped to prearranged heights by endless wind and its valleys converge on narrow veins of freshwater; everything is awash in sage and gold, naked for kilometres around. Here is a colony of black-tailed prairie dogs, yipping vigorously from honeycombed earth, and there a herd of restless pronghorn antelope, tearing across landscapes with an effortless trot. And on the banks of the Frenchman River, a lone bull.

I knew at once that this was a different class of bison: bigger, heavier, more regal than any I’d seen in Alberta, a coat of robust brown fur draped over a mountain of lumbering muscle. Elk Island seeded Grasslands with 71 bison in 2005 and those original 71 stayed relatively small their entire lives, stunted, however subtly, by their forested upbringing. But their children, born and raised on genuine prairie, assumed mightier dimensions. They also popped out faster, bringing the herd to 400 individuals by 2013. This is when the work of Ryan Hayes, bison operations coordinator, really began.

“We want to run this as a natural herd,” Hayes says, “and natural herds would usually deal with grizzlies, cougars and wolves. We don’t have any of that [here] anymore. So it’s our job to keep their numbers where they need to be for this landscape. If we ran too many bison, the grass would go downhill, and that would hurt everything, bison included.”

Some of the non-bison residents of Grasslands National Park. Clockwise from top left: black-tailed prairie dog; burrowing owl; coyote; pronghorn antelope; loggerhead shrike. Photos: Zack Metcalfe.

It’s a lot of work letting bison lead “natural” lives. In place of true migrations, Hayes trained them to follow a year-long circuit of their 45,000-acre enclosure, beginning and ending at the park’s bison-handling facility. Every other year they’re culled upon arrival, the selection both random and precise: random in that Hayes selects individuals without prejudice, precise in that he removes specific numbers from every age group. His goal is to mimic natural predation, which is hardest on the old and young.

“I think our herd has done a fantastic job holding on to its wild instincts,” Hayes says. “But we do have to gather them, we do have to handle them and we do have to bait them.”

He takes the herd from about 600 to 400 individuals, making sure – like an altruistic wolf – that they cannot overgraze the park. Of the 200 removed, a few of the oldest and unhealthiest are sent for “test slaughter” to confirm the absence among the herd of diseases such as brucellosis, tuberculosis and anthrax. A few more are sold as livestock. But whenever possible, as with Elk Island, excess bison go elsewhere, to establish new herds. This is the primary mechanism by which plains bison are repopulating North America.

Aside from this cull, the reality of the fence and the odd piece of alfalfa, Hayes practices non-interference in the bison’s daily lives. I could see this for myself in the lone bull on the Frenchman River, whom I found day after day in more or less the same place. He approached me once, slow and careful, reacting to the crunch of my boots and the click of my camera, but not to my movements. He closed the distance to a few unnerving paces and levelled his eyes in my general direction. Both orbs were milky white.

It’s a common injury among male bison, and it’s usually caused by other male bison. Unlike domestic herds, where bulls are kept to a minimum, wild herds have even sexes, and if one bull breeds 20 cows, there are 19 other bulls who won’t breed at all. This discrepancy is solved with violence.

“There are some pretty horrific fights,” from which discoloured eyes and hematomas often result, Hayes explains. But if a bull can still feed itself, water itself and protect itself from scavenging coyotes, it’s left alone. He’ll consider euthanasia if injuries are mortal, but he’s seen bulls thrive on three legs and impaired vision. They are, after all, wild.

I stayed in Grasslands the final week of May, when the park’s six or seven family groups – anywhere from 25 to 125 bison each – retreat deep into the prairie to birth their calves. And yet I saw bison – the several dozen bulls who’d lost the fight for parenthood – grazing through rewilding homesteads near the trail and road. They were eating crested wheatgrass planted for cattle a century before and lying down to rest by the ruins of old barns reclaimed by colonies of swallow. Most were gathering strength for breeding season, but the old bull on the Frenchman River probably wasn’t, too old and injured to keep up the fight, too content with his riverside prairie.

The place where bison jumped

Nearly 6,500 years ago, someone lit a fire in Wanuskewin, Saskatchewan. It’s the earliest act of human hands we’re aware of on this particular patch of prairie immediately northeast of modern Saskatoon, but far from the last. Over the millennia, people left behind campfire charcoal, teepee rings, clay pottery, medicine wheels, petroglyphs and spear tips dated to every intervening century. More than anything else, they left behind bison bones.

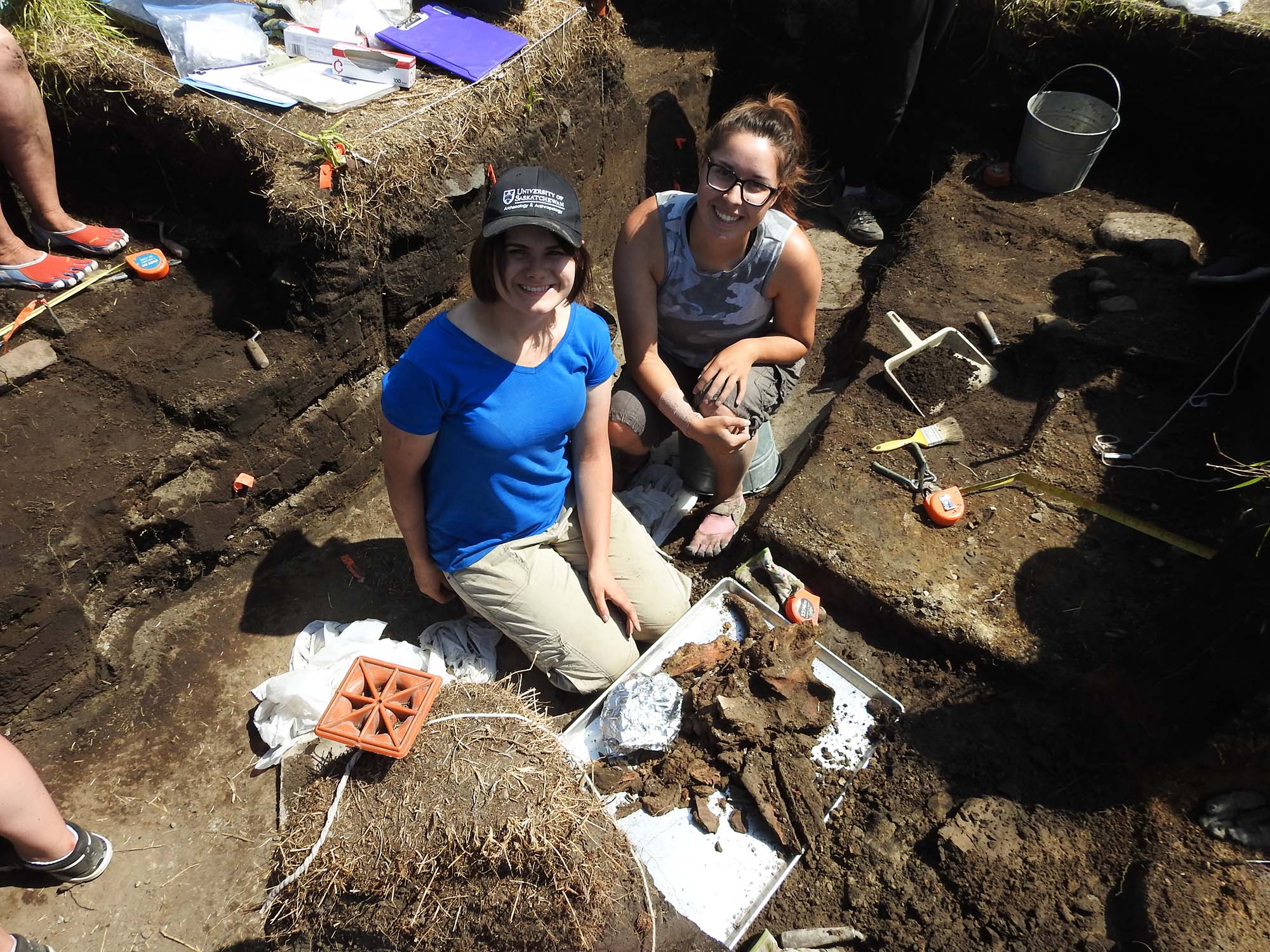

Wanuskewin is the longest-running archeological dig in Canadian history, lasting 41 consecutive years from the late 1970s until 2020. In that time, Wanuskewin transitioned from a private ranch to a 741-acre heritage park complete with interpretive centre and trail network, managed jointly by the provincial and federal governments, the University of Saskatchewan, the Meewasin Valley Authority and the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations.

Bison skull excavation archeology. Photos courtesy Wanuskewin.

Vance McNab sits on Wanuskewin’s board, representing George Gordon First Nation. He is Cree, one of six plains societies whose history is told at Wanuskewin, alongside Lakota, Nakoda, Dakota, Dené and Blackfoot. They and their antecedents once ran herds of bison off this park’s two “bison jumps,” steep slopes down which dozens of the beasts would be tricked into tumbling before slaughter.

McNab’s history with Wanuskewin is a long one. His grandfather, Hilliard McNab, was a driving force behind the park’s creation and an early ally of Dr. Ernie Walker, the archeologist who demonstrated the site’s historic value. Vance McNab even joined an archaeological dig at Wanuskewin while studying with the University of Saskatchewan. He unearthed a 2,000-year-old “Besant point” – the tip of a dart used in the hunt – on his first day.

“People had been digging in that spot for two weeks and hadn’t found anything,” McNab says. “So I was the miracle boy.”

The archeological record isn’t sensitive enough to distinguish one culture from another, he explains, but it does show the evolution of the hunt: how people killed and cooked bison at any given time and how their tools and methodologies changed over generations, from Besant points to forged arrowheads purchased from the Hudson’s Bay Company. It also shows when hunting in Wanuskewin began to dwindle – not with the eradication of bison, but with the arrival of horses to Saskatchewan in the early 1700s.

“At that time, plains people moved away from hunts where you forced bison into a trap or over a cliff,” McNab says. “Instead, you went out on your horse and caught bison any day.”

Scenes from Wanuskewin. Photos: Zack Metcalfe.

It’s easy to forget yourself in Wanuskewin. I toured its artifacts more than a little spellbound, reaching out unconsciously then recoiling sharply before flesh met stone. These tools, weapons and expressions of art show a connection with bison millennia deep, as fundamental as food to an empty stomach, as intimate as clothing in a prairie winter.

These are not overstatements. To understand them, one need only read reports of mass starvation from the 1870s, when at last the bison left Alberta and Saskatchewan. One 1879 dispatch from Edmonton House, Alberta, was especially clear in my mind as I lingered over shattered pots and beaded moccasins. “No buffalo,” it reads. “All on the plains [are] starving.” It’s only fitting, I thought, that First Nations return bison to Wanuskewin.

“Even in my grandfather’s time,” McNab says, “back in the early 1980s, they were talking about bringing bison here.”

It took time, money and the acquisition of land, but on December 7, 2019, six plains bison from Grasslands National Park made landfall in Wanuskewin. Only 10 days later, another five arrived from the United States, descended from the herds of Yellowstone.

“It sort of completes the story,” McNab says, “especially for the First Nations, who, all their lives, heard of how their ancestors survived on bison.”

In this regard, Wanuskewin is no longer unique. With the return of traditional territories to Indigenous peoples across the Great Plains, these same peoples have become champions of bison reintroduction. More recently, the Métis have been making moves.

“We’ve wanted to reintroduce bison to the land for quite some time,” says Michelle LeClair, vice-president of the Métis Nation of Saskatchewan. “We are the bison people. It was a no-brainer.”

Photos courtesy Métis Nation of Saskatchewan

In 2022, 1,700 acres were returned to the Métis Nation in and around the Batoche National Historic Site. By 2023 – with help from Parks Canada and Agriculture and Agri-Foods Canada – bison roamed the land. Their enclosure will eventually number 500 acres and the herd will grow to 100 individuals.

The Métis haven’t decided what to do with excess bison when the herd inevitably grows beyond capacity, but they have more territory, and other reintroductions are very much on the table – perhaps near Fort Qu'Appelle, says LeClair, or north of Prince Albert. Her only regret is that there’s so little land to give, relative to the historic range of bison.

“That’s the way it should be,” she says, “with wild herds on larger landscapes. We just don’t have the land. For us and for First Nations, who are really leading the charge, this has been our first opportunity to have bison return.”

Thinking bigger

Bison face the storm. It’s an old saying, and it’s meant literally. If clouds darkens the horizon, raining buckets on the next prairie over, bison will turn in that direction, staring wistfully at distant skies. This curious behaviour has lead some researchers – landscape ecologist Hila Shamon among them – to hypothesize that plains bison, like African wildebeest, track storm cells, making mental note of where the best grazing will soon be. The problem with this hypothesis is that it can’t be tested. If this is a part of their biology, no modern enclosure is large enough for them to express it.

“The species is being reintroduced and rewilded in some very large parcels,” Shamon says. “But their movements are still constricted. We don’t have any truly wild, free-roaming bison anywhere in North America.”

If you tally up all the “conservation herds” on the continent – those explicitly established to preserve the species under more or less natural conditions – the grand total is about 25,000 head, a far cry from the 25 million of the early 1800s. And if you tally up their enclosures, they roam about 0.5 percent of their historic range.

This is a problem, for land as well as for bison. Without large grazers, grasslands overgrow and smother themselves. And while cattle fill this niche admirably, there are important differences between these two ruminants. Bison shed great coats of fur, which are woven into nests for kilometres around, both for warmth and to mask the scent of chicks from predators. Bison also wallow, compressing the soil to form ephemeral ponds ideal for sensitive species of amphibian and wildflower. Their manure fosters kingdoms of dung beetle, nourishing soils and insectivores both. In places such as Wanuskewin, bison have even been recruited to aid in the destruction of invasive weeds and the spread of native seeds.

And then there’s grazing. Shamon has been scrutinizing adjacent grasslands in eastern Montana since 2018, some with bison, some with cattle. Among other things, bison are more mobile, grazing their grasslands into uneven mosaics with a wider variety of habitats. They’re also less dependent on water, straying farther from streams and rivers and leaving banks more vegetated. This means cleaner water and more reliable wildlife corridors. But for all the acres returned to plains bison and all the ecology they’ve set back into motion, their influence doesn’t reach far past the fence.

“Right now,” Shamon says, “plains bison are ecologically extinct.”

We don’t know how much land bison need for truly natural lives or to restore truly natural prairie. How far they’d migrate or graze or chase storms without a fence in their way is the million dollar question, Shamon says. To answer it, she’s tracked bison herds in 25,000-acre enclosures. These giants were in constant motion, perpetually bouncing off the fence.

“Like bees in a jar,” she says.

Indigenous-led reintroductions such as those at Wanuskewin and Batoche can have enormous cultural value, Shamon explains, but are presently too small and scattered to make an ecological dent relative to the Great Plains. Larger reintroductions – in Elk Island, Grasslands and even the 300,000-acre enclosure in Banff – also likely fall short. The best bet for bison, she says, is probably south of the border.

In eastern Montana, the American Prairie Foundation is purchasing private land between the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge and the Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument, connecting these and other federal lands to create a continuous 3.2-million-acre wildlife corridor through which they hope to run plains bison acquired from Elk Island National Park in 2009. If achieved, this so-called American Prairie Reserve could support a truly wild herd of 10,000 bison. At these scales, American prairie is the only game in town.

“If our goal is wild bison, behaving naturally on natural landscapes, then we need to think much bigger,” Shamon says. “We need to be more ambitious, even if that means making things more complicated. I’m sure there’s room in North America for bison. We just need to make space.”

Comments ()