When fire is a sign of hope

On using fire to save a butterfly (and countless other species), plus artists fighting for nature and a book to warm the spirit.

Change happens slowly, then all at once

The effect, at first, was discombobulating. Kat was driving through Banff National Park yesterday amidst a winter landscape straight off a postcard: white-capped conifers, a winding road, mountain peaks receding into the haze of falling snow. Then, to the left, a column of smoke and an orange glow appeared: flames, burning hot.

In the North American West, which has been devastated by wildfires in recent years, the first instinct is to panic – and to tell someone. But a sign on the highway preached calm: This is a planned burn, no need to report. And a quick online search confirmed that Parks Canada has been doing prescribed burns in the area. “Fires are necessary to improve forest health and reduce the long-term risk of wildfire to communities,” the government agency says. “Historical fire suppression has caused a significant decline in ecosystem health and diversity of species within the mountain national parks.”

It was a timely experience in light of our most recently published article on Fender's blue, a Pacific Northwest butterfly once thought lost and now poised to shift its status in a positive direction, from endangered to threatened. Efforts to restore this insect's habitat revealed a troubling truth: The upland prairie ecosystem needed by its host plant only exists because of disturbance, which historically was provided by fires managed by the Kalapuya people indigenous to the area. Restoring some of these cultural burning practices (as pictured above) helps make space for more host plants and create better conditions for caterpillars to survive.

One quote in the article really stuck with us: “The momentum is ripe right now to get that good fire on the ground.” The speaker is Colby Drake, burn boss and natural resources manager for the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, and amidst all the negative headlines about biodiversity loss, it's a beacon of hope. Change does happen. We can improve our land management practices and our relationship with nature. We just have to keep up the fight.

Stay wild,

Domini Clark and Kat Tancock, editors

P.S. Rewilding Arts Prize judges – including the three we profile below – will be meeting in the new year to review all the applications we received. We look forward to sharing the winners with you then.

The mural artist boosting awareness of urban ecology

In the streets and alleys of Canada’s biggest city, Nick Sweetman, aka “the bee guy,” has covered doors and walls with striking images of nature.

This printmaker uses plants as inspiration – and as ink

B.C. artist Edward Fu-Chen Juan creates silkscreened works of art that are rooted in both place and time and give a voice to nature.

These oversize bee sculptures help us see what’s really there

For Charmaine Lurch, rewilding starts with paying attention to the natural world around us – and learning how to listen.

The butterfly that saved an ecosystem

The revival of Fender’s blue illustrates the collaborative nature of survival.

How to design a forest fit to heal the planet

Reforestation and planting trees are crucial steps in the fight against climate change and biodiversity loss. But how do we do it the right way?

“In aggregate the world's peatlands resemble a book of wallpaper samples, each with its own design and character – some little more than water and reeds, others luxuriously diverse landscapes of colors we urban moderns never knew existed, silent sepia water, brilliant mosses, pale lichen, sundews like spilled water drops. And always they are in achingly slow motion that we cannot discern unless we keep measurement records – you can stand for a year and watch though you won't see a saltwater marsh silt up and become a fen. And always these places are under assault.”

– Annie Proulx, Fen, Bog & Swamp: A Short History of Peatland Destruction and Its Role in the Climate Crisis

Recommended reads

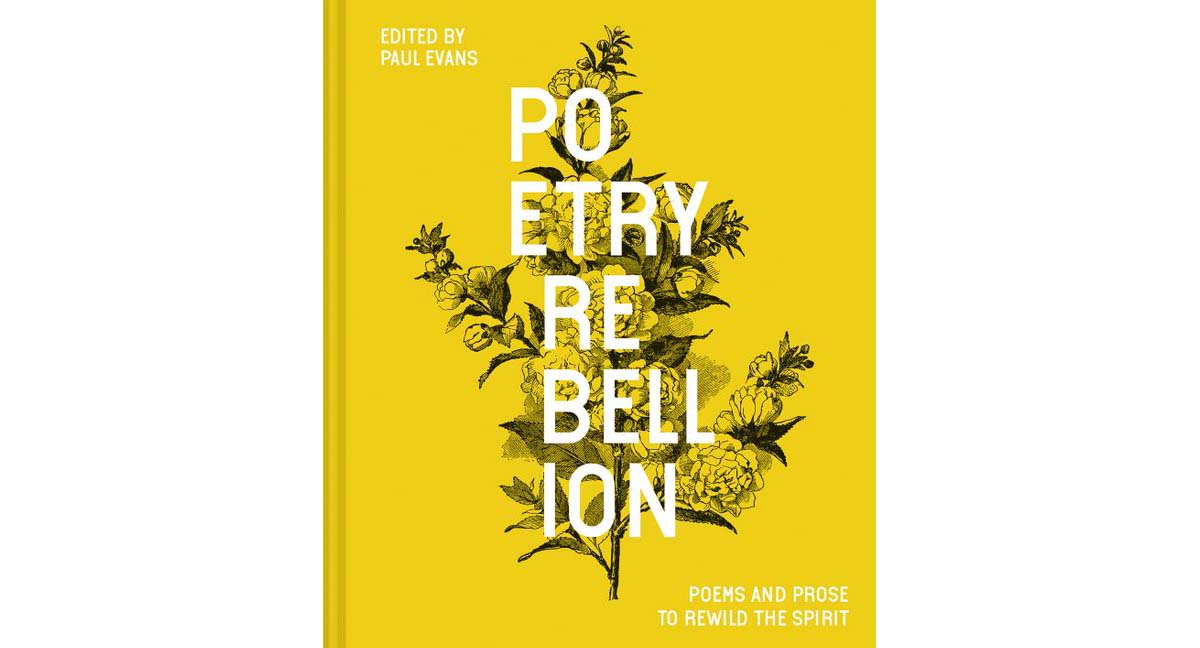

In the thoughtful essay that opens Poetry Rebellion, regular Guardian contributor Paul Evans explains that his intention with the book is “to reassemble some feelings, ideas, thoughts, dreams, facts that inspire a standing-up for Nature, and not just those parts of it we like or exploit.”

What follows is a collection of poems that spans 4,000 years, by authors ranging from Chaucer to Rachel Carson. Some are short – “Blackbird” is a mere four lines – while others fill pages (I’m looking at you, William Blake). Poetry is, of course, a deeply personal art form, so it’s unlikely every verse and stanza will stir your soul. But taken as a whole, the book is a charming, unexpected way to renew your will to keep fighting the good fight.

We encourage you to borrow Poetry Rebellion: Poems and Prose to Rewild the Spirit from your local library or purchase from an independent bookstore.

Elsewhere in rewilding

Here’s a surprising yet delightful pairing: Avant-garde Icelandic musician Björk and Braiding Sweetgrass author Robin Wall Kimmerer. In an audio interview for Artforum, they discuss language, nature and how the two intersect. “The whole idea that any of us is an individual is simply biologically not true,” says Kimmerer.

When a local estate owner and employer decided to put his land up for sale, the already declining Scottish town of Langholm faced major upheaval. But by teaming up to purchase the land for rewilding – touted here as the most ambitious such project in Britain – the community has new hope for the future.

Rewilding the American West with beavers and wolves is an undertaking with a lot of support amongst scientists, ranchers and other community members. But in the land of cattle, can it get enough political support?

“Down here in the U.S, or even in southern Canada, it is considered a triumph to conserve a parcel in the thousands of acres, while these Indigenous-led initiatives in Canada are conserving landscapes in the millions of acres.” A look at how First Nations and Inuit communities in northern Canada are addressing climate change and biodiversity loss by protecting land from resource development.

❤️ Enjoy this newsletter?

Send to a friend and let them know that they can subscribe, too.

Share your expertise: Do you know a project, person or story we should feature? Let us know.

Just want to say hello? Click that reply button and let us know what you think – and what else you'd like to see. We'd love to hear from you.

Comments ()